The surge in popularity of high-protein diets, from ketogenic regimens to paleo plans and carnivore protocols, has ushered in a wave of questions about long-term health impacts. While protein is essential for muscle repair, metabolic health, immune function, and satiety, concerns linger about its potential downsides. Among the most frequently debated topics is this: will too much protein cause kidney stones and harm your health? This question has found its way into dietitian consultations, fitness forums, and medical clinics alike, driven by both anecdotal experiences and emerging scientific inquiries.

You may also like : The Ultimate Guide to Choosing a High Protein Diet Name That Fits Your Goals

Understanding Protein Metabolism and Kidney Function

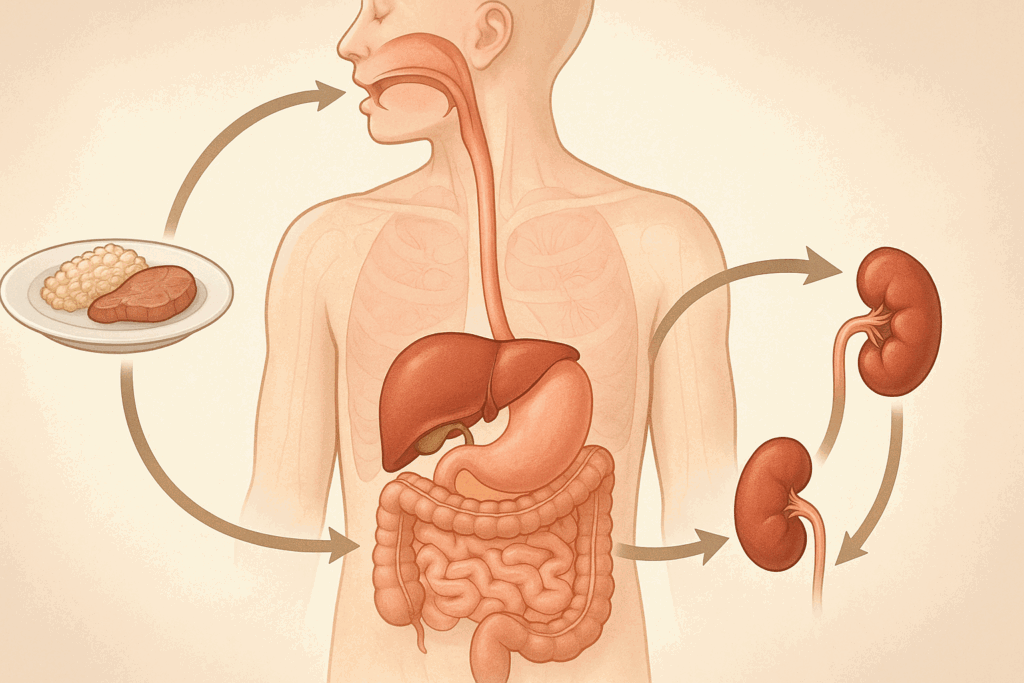

To understand whether high-protein diets pose a risk to kidney health, we must first explore how protein is metabolized in the body and the role kidneys play in this process. Proteins are made of amino acids, which undergo deamination in the liver, a process that removes the amino group and generates ammonia as a byproduct. The liver converts ammonia into urea, which is then transported to the kidneys for excretion through urine. This metabolic cycle places a certain workload on the kidneys, particularly in eliminating nitrogenous waste.

Healthy kidneys are designed to handle this task with remarkable efficiency. However, questions arise when individuals increase protein intake far beyond dietary guidelines, sometimes exceeding 2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight per day. This elevated intake leads to a corresponding increase in urea production, potentially raising the filtration demands placed on the kidneys. While this doesn’t automatically spell danger for healthy individuals, it raises legitimate concerns for those with pre-existing kidney dysfunction or genetic predispositions.

The Mechanisms Behind Kidney Stone Formation

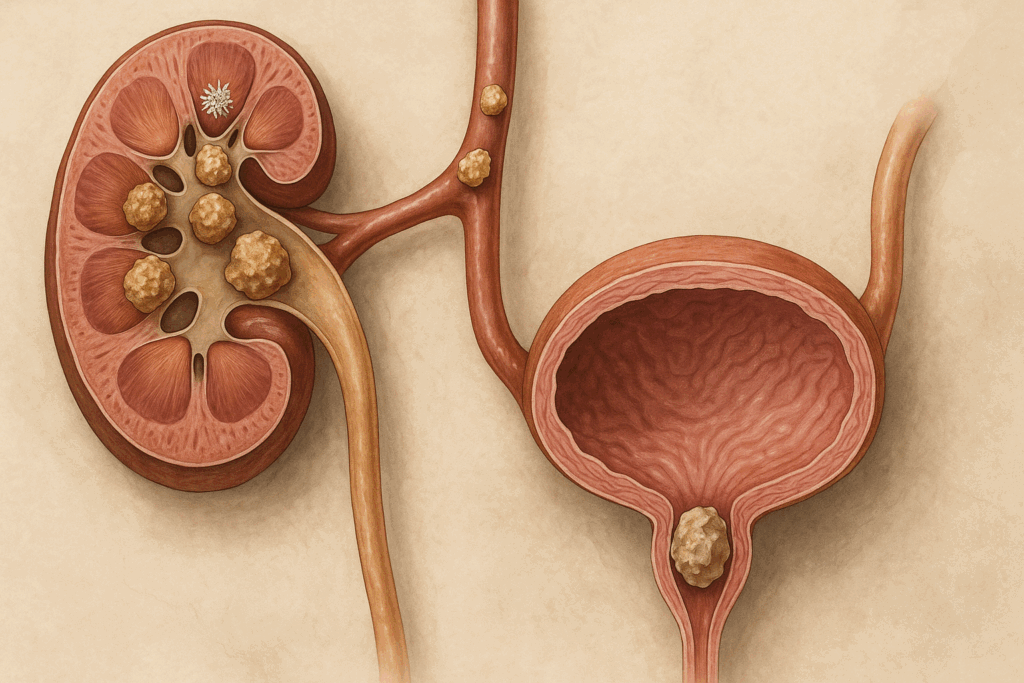

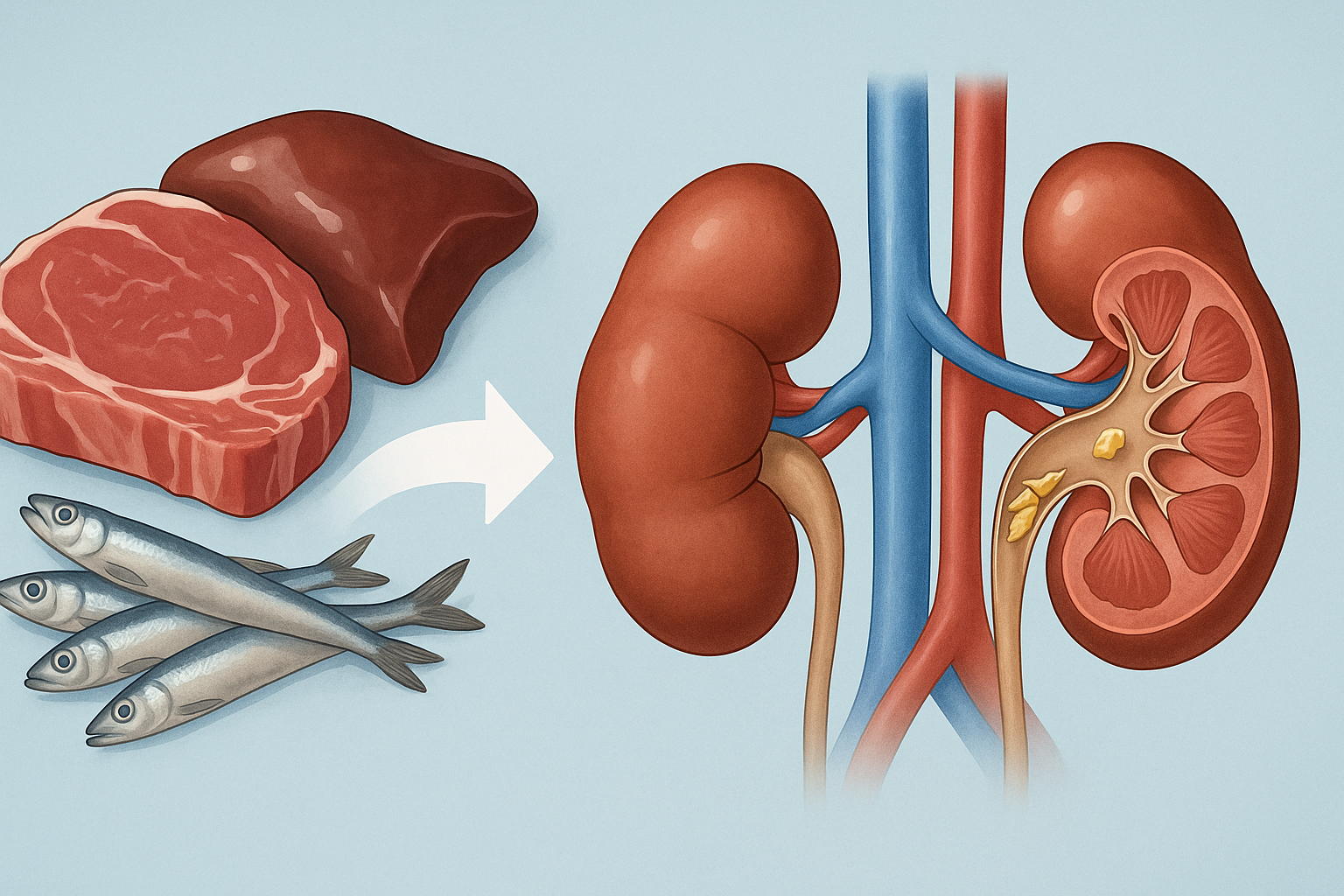

Kidney stones, or renal calculi, are crystalline mineral deposits that form in the urinary tract. The most common type, calcium oxalate stones, can result from a variety of dietary and physiological factors. These include dehydration, high urinary calcium or oxalate, low urinary citrate, and elevated urinary uric acid. Protein intake intersects with several of these mechanisms.

High animal protein consumption, in particular, has been shown to lower urinary pH, promoting an acidic environment conducive to uric acid stone formation. It also increases calcium excretion (hypercalciuria) and reduces citrate levels, both of which can favor the formation of calcium-based stones. Importantly, not all proteins have the same effect: plant-based proteins are generally associated with a lower risk profile, possibly due to their alkalinizing effects and fiber content.

Will Too Much Protein Cause Kidney Stones in Healthy Individuals?

One of the most contentious questions in nutrition science today is whether consuming large amounts of protein—especially from animal sources—can cause kidney stones in otherwise healthy people. Clinical trials and epidemiological studies offer mixed results. Some research suggests a positive association between high animal protein intake and kidney stone risk, particularly in populations with inadequate fluid intake or existing risk factors like obesity or a sedentary lifestyle. Conversely, other studies indicate that protein’s role is more correlative than causal, with stone risk significantly modulated by hydration status, overall diet quality, and genetic predisposition.

A 2019 meta-analysis published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition concluded that high protein diets increased urinary calcium excretion but did not consistently elevate stone incidence when fluid intake was adequate. This underscores a critical nuance: the problem may not lie solely in protein intake, but in the context in which it occurs. For example, diets high in sodium or low in potassium can exacerbate calcium stone risk, even at moderate protein levels.

Can a High Protein Diet Cause Kidney Stones in At-Risk Populations?

Individuals with a history of kidney stones, chronic kidney disease (CKD), or metabolic syndromes like diabetes or hypertension may be more susceptible to the adverse effects of high-protein diets. In such cases, even moderate increases in dietary protein may accelerate the progression of kidney impairment or stone formation. Clinical guidelines often advise these individuals to limit protein intake to below 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day, focusing more on quality rather than quantity.

Moreover, certain genetic conditions like cystinuria or primary hyperoxaluria directly influence stone formation pathways, making dietary protein moderation even more crucial. For these groups, the question shifts from “can a high protein diet cause kidney stones?” to “how can we tailor protein intake to minimize renal stress without compromising nutritional adequacy?” In such contexts, consultation with a nephrologist and registered dietitian is essential for crafting a sustainable dietary plan.

Differentiating Between Animal and Plant Proteins in Kidney Stone Risk

Another layer of complexity arises when differentiating the effects of animal versus plant proteins on kidney stone formation. Animal proteins tend to increase acid load and sulfur-containing amino acid metabolism, both of which may reduce urinary citrate and increase calcium excretion. They also tend to be lower in magnesium and potassium, two minerals that can help inhibit stone formation.

Plant proteins, by contrast, generally contribute to a more alkaline urinary environment and are accompanied by beneficial nutrients like fiber, antioxidants, and phytochemicals. Studies have shown that diets emphasizing legumes, nuts, and seeds over red meats and processed meats are associated with a lower incidence of kidney stones. Therefore, it is not just the quantity but the type of protein consumed that matters.

Will Too Much Protein Cause Kidney Stones in the Context of Fitness and Bodybuilding?

The fitness and bodybuilding communities often advocate protein intakes that exceed 2.5 grams per kilogram of body weight, aimed at optimizing muscle hypertrophy and recovery. This has led to concerns about whether such high protein consumption over months or years might increase the risk of kidney stones or impair renal function.

So far, the evidence suggests that high-protein diets in healthy athletes do not necessarily lead to kidney damage or stone formation, provided hydration is maintained and dietary balance is respected. However, long-term data are limited. A 2020 study in Nutrients involving resistance-trained individuals found no significant change in kidney function markers over a one-year period, despite high protein intakes. Nonetheless, this does not preclude the possibility of issues arising over decades, especially in the presence of unrecognized risk factors.

Practical Dietary Guidelines for Minimizing Kidney Stone Risk

For individuals committed to a high-protein lifestyle but concerned about kidney health, several practical strategies can mitigate risk. First and foremost, maintaining adequate hydration is critical. Water dilutes urinary solutes and reduces the concentration of stone-forming minerals. Aim for at least 2.5 liters of fluid daily, more if engaging in strenuous activity or living in hot climates.

Second, balance is key. Incorporating plant-based proteins such as beans, lentils, and quinoa can reduce dietary acid load and provide protective micronutrients. Simultaneously, limiting sodium intake helps reduce calcium excretion, while increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables boosts potassium and citrate levels, both of which inhibit stone formation.

Third, those with known risk factors or previous stones should consider undergoing a 24-hour urine analysis and working with a dietitian to personalize their macronutrient intake. Monitoring urinary pH, calcium, oxalate, and citrate can offer invaluable insights into individual susceptibility and inform dietary modifications that reduce risk without compromising nutritional goals.

Exploring the Science: Can a High Protein Diet Cause Kidney Stones Across Populations?

The global rise in protein consumption, especially in industrialized nations, has sparked a growing interest in cross-cultural studies examining kidney stone prevalence. For example, populations adhering to Mediterranean or plant-based diets often report lower stone incidence compared to those following Western-style diets high in red meats and processed foods. Such findings suggest that lifestyle factors, including physical activity, hydration habits, and dietary patterns, may have a more pronounced effect on stone formation than protein intake alone.

Additionally, genetic epidemiology studies have begun identifying polymorphisms associated with stone susceptibility, shedding light on why some individuals form stones despite modest protein consumption while others remain stone-free on high-protein diets. These insights pave the way for more personalized dietary recommendations that take into account not only macronutrient composition but also individual genetic, metabolic, and environmental factors.

Will Too Much Protein Cause Kidney Stones When Combined With Other Risk Factors?

One of the most crucial dimensions of this discussion lies in the interplay between high protein intake and other dietary or lifestyle risk factors. Excess sodium, low fluid intake, high sugar consumption, and low intake of calcium can all contribute to an environment conducive to stone formation. In such cases, high protein intake may act as a compounding variable rather than a primary cause.

For instance, diets high in processed meats often contain substantial amounts of sodium and phosphorus additives, both of which have been implicated in kidney stress and mineral imbalances. Similarly, individuals consuming high-protein, low-carb regimens may experience increased ketone production, leading to mild dehydration and aciduria, both of which can elevate stone risk. This context reinforces the importance of evaluating dietary patterns as a whole, rather than isolating individual nutrients.

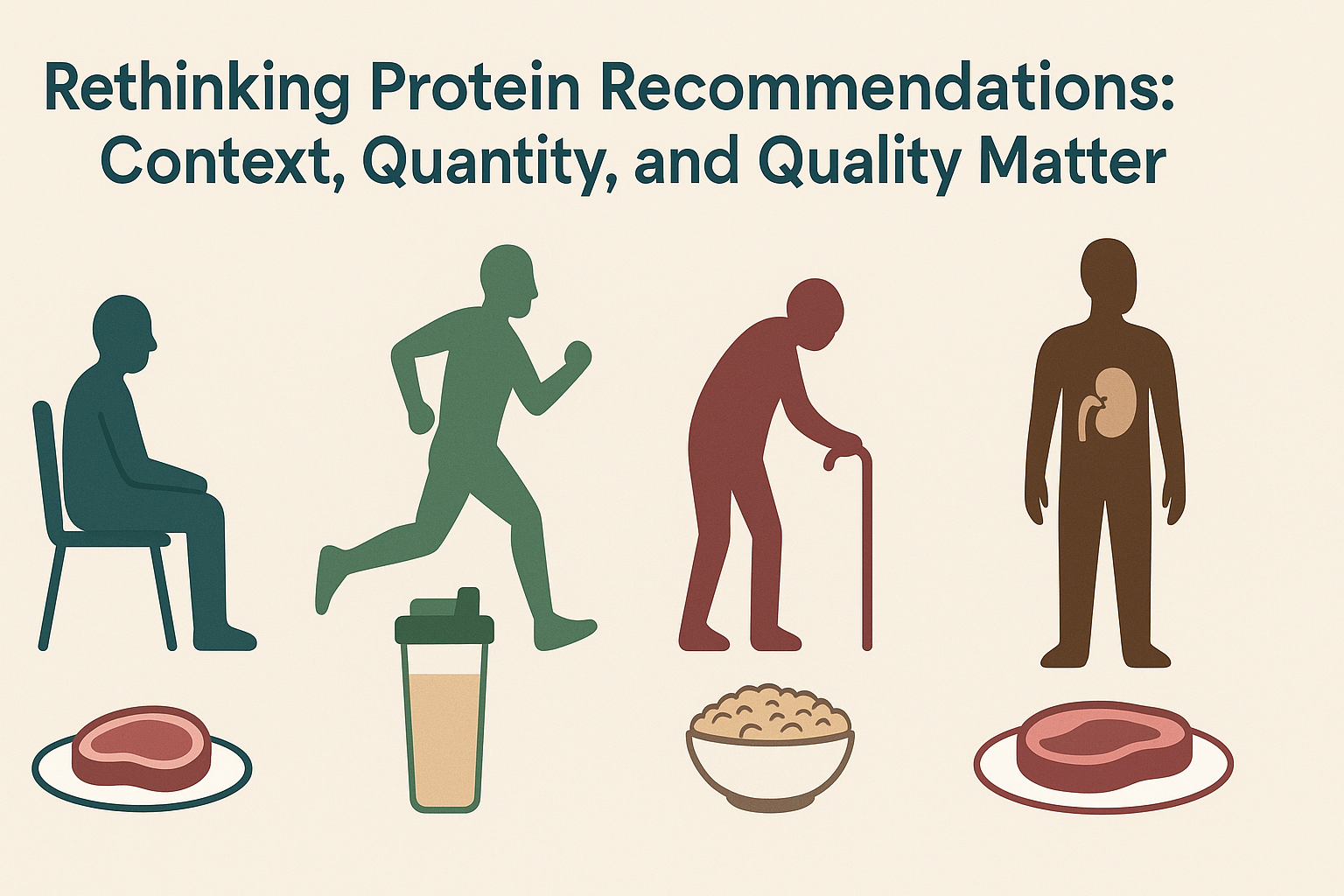

Rethinking Protein Recommendations: Context, Quantity, and Quality Matter

Current dietary guidelines recommend 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for sedentary adults, with increased needs for athletes, older adults, and those recovering from illness or injury. However, the trend toward significantly higher intakes has outpaced the supporting evidence, especially when it comes to long-term health outcomes.

Emerging research supports a more individualized approach that considers total caloric intake, physical activity levels, health status, and food quality. For example, a physically active adult may benefit from 1.4 to 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, provided their renal function is uncompromised. Within this range, plant-based sources should be prioritized or at least integrated to balance acid load and provide essential phytonutrients.

Ultimately, rather than asking whether protein is inherently harmful, a better question might be: under what conditions does protein become a liability rather than an asset? This perspective encourages more nuanced dietary planning and fosters a holistic view of nutrition.

Phytate: An Antinutrient or a Stone-Preventing Ally?

Phytate, a naturally occurring compound in whole grains, legumes, and seeds, has historically been labeled as an “antinutrient” for its role in inhibiting mineral absorption. However, recent studies have demonstrated its potential to inhibit calcium oxalate crystal formation in the kidneys. Phytate binds calcium and prevents its interaction with oxalate in urine, thereby reducing stone risk.

While excessive phytate may reduce mineral bioavailability in poorly planned diets, it appears to be protective when consumed as part of a balanced, nutrient-rich diet. This has major implications for the design of high-protein meal plans that include whole plant foods.

Emerging Plant-Based Alternatives: Protein Without the Stone Risk?

The growing market for plant-based protein powders and meat substitutes has opened new avenues for those looking to increase protein intake without raising kidney stone risk. Pea protein, rice protein, hemp, and soy-based products offer high bioavailability and essential amino acids without the acid load or purine content of many animal proteins.

Moreover, these plant-based options often contain additional components like fiber, magnesium, and potassium, all of which support renal health. As the food industry evolves, these alternatives could become central to dietary strategies that support high protein intake while minimizing potential harms.

Protein Timing and Distribution: Does Meal Frequency Matter?

An area of inquiry that has garnered less attention is the timing and distribution of protein intake throughout the day. Many high-protein diet adherents front-load or back-load their intake, consuming large amounts at a single meal. Emerging evidence suggests that spreading protein intake more evenly throughout the day may reduce the burden on renal filtration and improve nitrogen balance.

This even distribution could also minimize postprandial spikes in urea and other metabolites, giving the kidneys a more manageable workload. While the impact on stone formation specifically has yet to be fully studied, there is reason to believe that meal timing could become another lever for reducing renal stress without compromising dietary goals.

Hormonal Influences: Gender Differences in Protein Processing and Stone Risk

Gender-specific hormonal profiles can influence how the body responds to dietary protein and regulates calcium metabolism. For example, estrogen enhances calcium absorption and inhibits bone resorption, which could theoretically reduce urinary calcium and, by extension, stone risk. Premenopausal women may be relatively protected against protein-induced hypercalciuria compared to men or postmenopausal women.

Moreover, testosterone may influence oxalate handling by the kidneys, possibly increasing susceptibility in males. These sex-specific physiological differences highlight the importance of considering gender when evaluating the impact of high-protein diets on renal outcomes.

Environmental and Lifestyle Modifiers: Beyond Diet Alone

While dietary protein intake is a key variable, environmental and lifestyle factors can either amplify or buffer its impact on kidney health. Hydration remains the most critical modifiable factor. Even among high-protein consumers, those who maintain optimal hydration exhibit a significantly lower incidence of kidney stones. Inadequate fluid intake concentrates urine and increases the likelihood that solutes like calcium and oxalate will crystallize.

Climate and physical activity also play a role. People living in hot, arid environments or those engaged in intense physical labor or athletic training lose more fluids through sweat, further concentrating urine if fluid intake isn’t increased accordingly. Thus, recommendations for protein intake should always be contextualized within broader lifestyle and environmental frameworks.

Uric Acid and Purine Metabolism: A Hidden Culprit in High-Protein Diets

Another often-overlooked mechanism by which high-protein diets may promote kidney stones involves purine metabolism. Purines are natural substances found in high concentrations in red meat, organ meats, and some seafood. When metabolized, purines produce uric acid. An excessive intake of purine-rich foods can result in hyperuricemia (elevated blood uric acid) and hyperuricosuria (excess uric acid in urine), both of which can lead to the formation of uric acid stones.

Unlike calcium oxalate stones, uric acid stones tend to form in more acidic urine. High-protein diets can lower urinary pH, especially when carbohydrate intake is restricted (as in ketogenic diets). This acidic environment, combined with high uric acid levels, creates the perfect storm for uric acid stone formation. Adjusting the protein source and ensuring a sufficient intake of alkalizing vegetables can help mitigate this risk.

The Gut-Kidney Axis: How Microbiota Mediate Stone Risk

One of the most compelling new areas of investigation is the gut-kidney axis. Research shows that gut bacteria can play a significant role in metabolizing compounds that influence kidney stone formation. Of particular interest is Oxalobacter formigenes, a beneficial bacterium that degrades oxalate in the intestine, reducing its absorption and subsequent excretion by the kidneys.

High-protein diets, especially those rich in animal sources, may negatively impact gut microbiome diversity by reducing populations of beneficial bacteria, including O. formigenes. This imbalance can lead to increased oxalate absorption and higher urinary oxalate concentrations—a known risk factor for calcium oxalate stone formation. Future dietary recommendations may focus not only on protein type and quantity but also on how they affect microbial ecology, which in turn influences kidney health.

The Role of Dietary Acid Load and Renal Acid Excretion

Another emerging factor is the impact of dietary acid load. Animal proteins, especially from red meat and eggs, contain sulfur-containing amino acids like methionine and cysteine. When metabolized, these amino acids produce sulfuric acid, increasing the body’s acid load. In response, the kidneys excrete more acid and calcium to buffer the systemic pH, which can lead to hypercalciuria and contribute to stone formation.

Interestingly, not all individuals respond the same way to increased acid load. Genetic polymorphisms in renal tubular transporters and acid-base regulation mechanisms may influence a person’s ability to compensate. Some people may excrete more calcium than others under identical dietary conditions, pointing to the need for personalized dietary interventions.

Metabolomics and Stone Precursors: Early Biomarkers of Risk

The use of metabolomics in nutrition and nephrology is shedding new light on early indicators of kidney stone formation. Metabolomics refers to the large-scale study of small molecules, or metabolites, within cells, tissues, or fluids. Researchers have begun identifying metabolic signatures that precede kidney stone formation, including elevated levels of hydroxyproline, a breakdown product of collagen that may reflect high meat consumption.

Some metabolites associated with high-protein diets—such as trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO)—have been linked to both cardiovascular and kidney disease. Though not yet conclusively associated with stone formation, these metabolites may contribute to renal inflammation or oxidative stress, indirectly increasing stone risk. This area of research is still in its infancy, but it promises to provide early detection tools and deepen our understanding of how protein influences long-term kidney health.

The Role of Preventive Screening and Professional Guidance

For those with concerns about kidney health or stone formation, preventive screening offers a critical window of opportunity. A comprehensive metabolic panel, 24-hour urine analysis, and renal ultrasound can detect early signs of kidney stress or stone formation. These diagnostics, when interpreted by healthcare professionals, can guide dietary choices that support both fitness and renal health.

Furthermore, professional guidance is invaluable when embarking on high-protein diets. A registered dietitian can help structure a macronutrient profile that supports muscle maintenance and weight management while minimizing renal strain. They can also identify nutrient imbalances, recommend supplements if necessary, and ensure that hydration and electrolyte needs are met.

The Psychological Dimension: Dietary Adherence and Health Anxiety

The psychological effects of health trends also warrant discussion. The fear of kidney damage has led some individuals to avoid protein-rich foods entirely, potentially compromising muscle mass, immune function, and metabolic health. On the other hand, blind adherence to high-protein regimens without medical oversight can lead to unrecognized health issues.

Balanced, evidence-based guidance is essential to avoid extremes on either end. Public health messaging should focus on individualized risk assessment and encourage informed dietary choices rather than fear-based avoidance or uncritical enthusiasm.

Frequently Asked Questions: Will Too Much Protein Cause Kidney Stones?

1. How does long-term high protein intake affect kidney filtration over time?

While short-term high protein diets are generally safe for healthy individuals, long-term intake may increase glomerular pressure and filtration rate in the kidneys. This condition, known as hyperfiltration, is a compensatory mechanism that can place sustained stress on the nephrons. Over decades, especially when hydration is suboptimal or when combined with other dietary risks like high sodium, this could lead to subtle structural changes in kidney tissue. Though not conclusively linked to chronic kidney disease in healthy people, individuals with undiagnosed kidney vulnerabilities may be more susceptible. In such contexts, the concern that “will too much protein cause kidney stones” becomes more relevant, particularly if preventative measures are not in place.

2. Can a high protein diet cause kidney stones in athletes who consume protein supplements daily?

Athletes often consume protein supplements to meet recovery and muscle growth goals, but this practice, when not balanced with hydration and electrolyte intake, may elevate the risk of kidney stone formation. The metabolism of excess amino acids generates nitrogenous waste, primarily urea, which is excreted through the kidneys. If urine becomes overly concentrated—common in dehydrated or high-sweating athletes—the minerals like calcium, oxalate, or uric acid may crystallize into stones. While the athletic population is typically healthy, the question “can a high protein diet cause kidney stones” is valid when intake exceeds bodily requirements or when fluid intake is inadequate.

3. What role does hydration play in mitigating the risk of kidney stones from high protein intake?

Hydration is a critical variable in the equation of kidney stone risk. Proteins increase the excretion of waste products like urea and uric acid, which must be diluted in urine. If fluid intake is low, urine becomes more concentrated, fostering an ideal environment for stone-forming crystals. Even if your protein consumption is high, consistently drinking enough water—especially before, during, and after meals—can significantly reduce your risk. Addressing the concern “will too much protein cause kidney stones” often comes down to whether or not the body has sufficient fluids to flush out excess compounds effectively.

4. Are plant-based proteins less likely to contribute to kidney stone formation?

Yes, plant-based proteins generally result in lower acid load and lower excretion of stone-promoting compounds compared to animal-based proteins. This is because plant proteins often come with additional beneficial nutrients such as magnesium, potassium, and phytates, which may inhibit stone formation. Furthermore, vegetarian diets tend to be higher in fiber and lower in sulfur-containing amino acids, reducing the acidifying effect on urine. While both plant and animal proteins are metabolized by the kidneys, individuals wondering “can a high protein diet cause kidney stones” may consider substituting part of their animal protein intake with legumes, tofu, or quinoa to reduce the overall burden.

5. Will too much protein cause kidney stones in people with no prior history of kidney issues?

In healthy individuals without a personal or family history of kidney stones or chronic kidney disease, moderate to high protein intake is generally safe. However, the margin for excess is not infinite. Over time, consistently exceeding protein requirements—especially from animal sources—can elevate urinary calcium and decrease citrate, a natural inhibitor of stone formation. The answer to “will too much protein cause kidney stones” in this context depends on other dietary and lifestyle factors, such as fluid intake, genetic predisposition, and consumption of oxalate-rich or sodium-heavy foods.

6. How does the acid load from protein-rich foods influence stone formation?

Animal proteins, especially red meat and seafood, increase the production of sulfuric acid during digestion, which lowers urinary pH. Acidic urine promotes the formation of uric acid and cystine stones. Moreover, chronic acidosis may lead to bone resorption, releasing calcium into the urine, another risk factor. People often overlook the role of acid-base balance in kidney health, focusing solely on macronutrient counts. Addressing the nuanced question “can a high protein diet cause kidney stones” requires understanding that dietary acid load—not just protein quantity—plays a significant role in the stone-forming process.

7. Will too much protein cause kidney stones if you’re following a ketogenic or low-carb diet?

Low-carb and ketogenic diets often rely heavily on protein and fat, with limited carbohydrate intake. While these diets may have metabolic benefits, they can increase urinary calcium and decrease citrate levels, both of which are associated with a higher risk of kidney stone formation. Ketogenic diets can also lead to low urinary pH, further contributing to stone risk, especially uric acid stones. People following such diets should be particularly vigilant about hydration and consider potassium citrate supplementation if advised by a healthcare provider. The potential for “will too much protein cause kidney stones” becomes more significant in the context of these restrictive dietary patterns.

8. Can adjusting your calcium intake help balance protein-related kidney stone risk?

Surprisingly, increasing dietary calcium—not decreasing it—can help reduce the risk of kidney stones in the context of high protein diets. Adequate calcium binds to dietary oxalates in the intestines, preventing their absorption and subsequent excretion through urine. This reduces the chances of calcium oxalate stones, the most common type. Calcium from food sources is preferable to supplements, which may have the opposite effect. If you’re concerned that “can a high protein diet cause kidney stones,” ensure you’re getting calcium from leafy greens, dairy, or fortified alternatives as part of your daily intake.

9. What populations should be most cautious about high protein diets and kidney stone risk?

Certain individuals are at a higher risk of adverse effects from high protein consumption. These include people with a personal or family history of kidney stones, those with single kidneys, and individuals with reduced kidney function or metabolic disorders affecting calcium or oxalate metabolism. For these populations, the likelihood that “can a high protein diet cause kidney stones” shifts from theoretical to practical. Tailored dietary planning with a nephrologist or dietitian is recommended to balance protein needs with kidney preservation strategies.

10. Will too much protein cause kidney stones as you age, even if you’ve tolerated it in youth?

Aging brings natural declines in kidney function, often unnoticed until late stages. What your kidneys could handle at 25 may become burdensome at 65. Muscle mass declines with age, but protein needs may increase slightly to counteract sarcopenia. However, the kidneys may not process the same high loads as efficiently, especially in the presence of hypertension or type 2 diabetes—two common age-related conditions. Therefore, the risk that “will too much protein cause kidney stones” becomes more significant with age, and ongoing nutritional evaluation is crucial for long-term renal health.

Conclusion : Will Too Much Protein Cause Kidney Stones and Harm Your Health?

While high-protein diets have clear benefits for satiety, muscle mass, metabolic rate, and weight management, they are not without potential drawbacks—particularly when practiced without balance or oversight. For healthy individuals with adequate hydration, the current evidence suggests that increased protein intake does not inherently cause kidney stones or long-term renal damage. However, the risk becomes more pronounced in the presence of other factors: high sodium intake, poor hydration, excessive animal protein, genetic predispositions, or pre-existing kidney disease.

So, will too much protein cause kidney stones and harm your health? The answer depends on context. For most healthy adults, mindful dietary choices and sufficient fluid intake can mitigate risks. But for those with elevated risk profiles, a more conservative approach—informed by clinical evaluation and nutritional guidance—is both prudent and necessary.

In the evolving conversation about protein and kidney health, one truth remains clear: knowledge is power. Understanding the variables at play empowers individuals to craft a dietary plan that supports their goals without compromising long-term wellness. As science continues to unravel the complex interplay between diet and disease, embracing nuance over absolutism will be key to making informed, health-promoting choices.